I realize that though I wrote about Hoover Dam in Unending Wonders of a Subatomic World, the event was streamlined, couched in comedy taking advantage of Hope and Chance wrangling life on The Road.

I will now try to impart a little of what my virgin experience of Hoover Dam was like.

One grows up hearing about the Hoover Dam, several paragraphs perhaps devoted in the history books at school. One grows up hearing about Hoover Dam as a monumental technological achievement that grew out of the Depression. Accompanying are stock photos that never quite express the size of it, but even if they did they are so bled dry and sterile that, years later, if one is traveling toward the dam one expects that same school page experience with the black and white text surrounding. Flat. No peril. No magic. No taste of the awe that is supposed to be inspired by one of the so-called wonders of the world.

One views a photo of a daredevil artist balancing on one hand on a teeter-totter chair propped on one leg on a fifty story high girder, their life an unexpected hiccup of indiscriminate wind away from a death tumble into the abyss of the city streets far below, and the viewer's year's-distant balance falters and woozily swims with the knowledge of how thin is the thread that holds us to the here and now solid ground. Out of balance, the viewer falls into the pit and is gone, even as the daredevil artist, in the next never seen photo, ably cheats death and safely descends.

Yet photos of the Hoover Dam, despite all the power generated by it, are about as thrilling as white, orthopedic shoes.

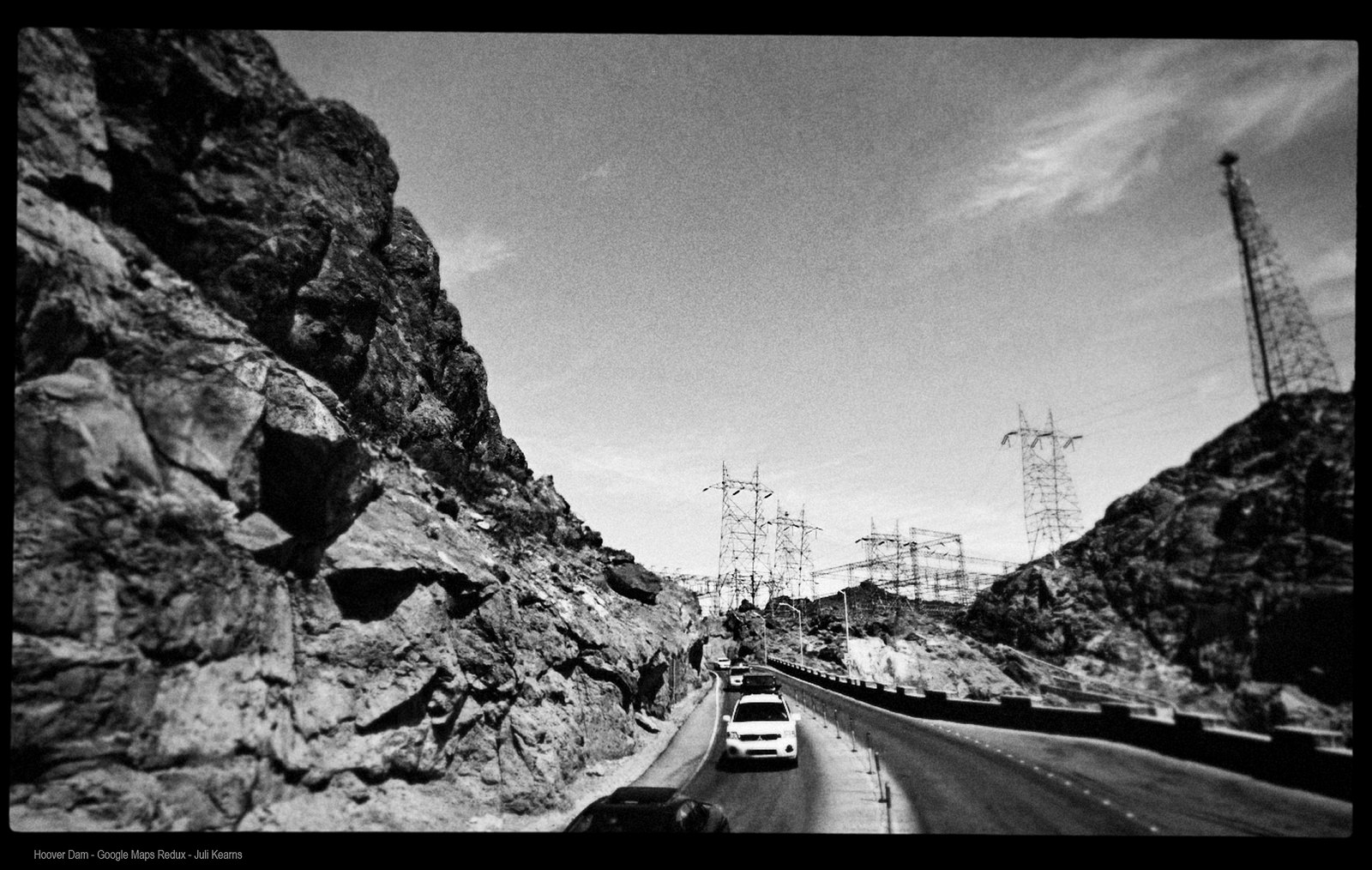

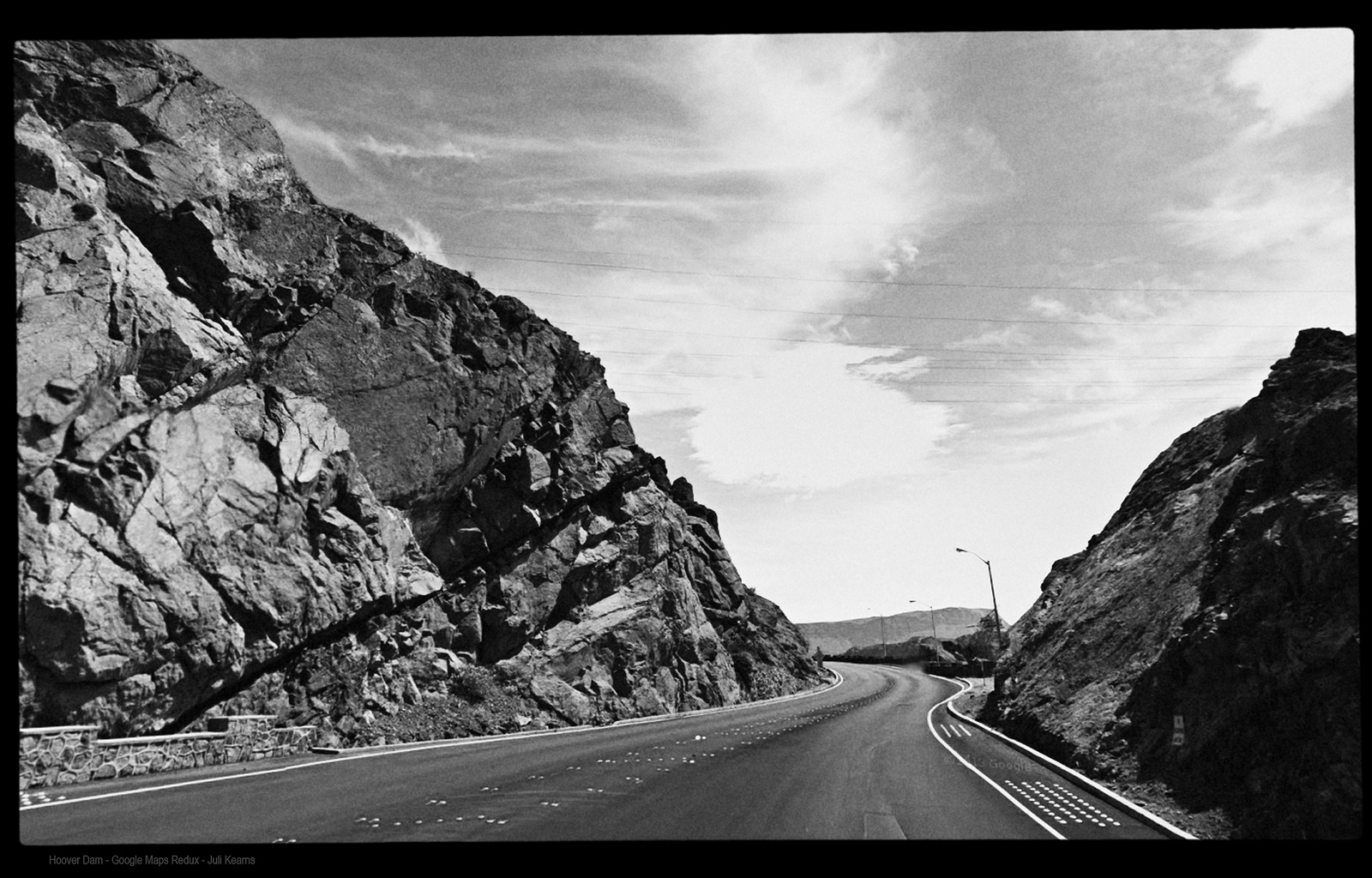

Was it around midnight as we drove toward Hoover Dam, I forget, because memory is a chaotic box of tumbling rock crushing instead of polishing ant-sized comprehensions. We were surrounded by Mack trucks and blasted canyon wall, adrenaline building with the interminably long bottleneck funnel of the highway and the forward crushing flow of the bumper to bumper traffic, like an amusement park roller coaster ride in its downward-bound submission to gravity with one's heart in one's throat. Trapped in the river of vehicular metal crowding insecure flesh, kept to the mountain curves of the narrow road by the rock through which it's been tunneled, though one has the confidence of "odds are" everything's going to be all right, when the interstate is wet and the breaks of so many big trucks are screaming around you in the dark, one gets edgy. On the map, one might note the curving road that will deliver you finally at Hoover Dam, but you don't see the rocks and the mack trucks and the grinding long descent with what may be spacious skies above during the day but at night that blue turns black and becomes a boxed tunnel. At the end, you're still expecting, because of those school books and the public education movies, a grainy film clip of Hoover Dam, which you're even looking forward to viewing in real life, because it is called one of the Wonders of the World, though you know there will be no climax from which to decompress with an anticlimactic release of "wow, that was amazing" tension.

The light at the end of the tunnel effect sometimes occurs with such blinding impact that instead of safe relief and release one crashes into it. Which is what it was like at the end of the last curve when we were unexpectedly thrown onto the open road perched 700 feet high above the Colorado River. A briefly glimpsed sign to the side read everyone should stay in their cars. And then we could finally see rather than just feel the flow of the bumper to bumper traffic in the spotty brilliance of the lamps shining down on the dam and the slim river of cars and trucks coursing over it, almost completely at a standstill now, as individuals jumped from their vehicles and ran towards, oh my god, angels, Hoover Dam was in the middle of an end-of-days, apocalyptic scenario, with people rushing ecstatic to kiss the feet of massive angels that suddenly soared overhead, art deco stolid, their severe wings folded tight. Though traffic was slow, and people weaved between to reach the angels, somehow flow was still insistent enough, that once I grasped that all these people were participants in a mass communion of some good luck ritual with roots in superstitions more ancient than the Egyptian pyramids, the moment was past, the angels were behind us and we were now over the dam proper, continuing on.

Hindsight knowledge is we happened to have driven through Las Vegas during the blow out of an end of the season college basketball championship being held there and every inch, even the streets, was standing-room-only packed with hopeful gamblers and ambulances in the drop-off lane outside every gambling palace.

One never hears about the angels at Hoover Dam. Pictures of them don't capture their size and only a little of their severity as they overlook where 114 men died during the dam's construction. The angels seem as small figures, perhaps because of their slimness, when their feet are positioned to accept supplication and their wings are thirty feet tall.

It was that Hoover Dam night that the alternator of the car went out, during our Great Penguin trip, and we were stranded the next day in Kingman, Arizona while a snowstorm barreled in toward us.

Return to this book's main page for more information, FAQ, and the first chapter in PDF form.

Return to "Sightseeing" Unending Wonders of a Subatomic World (or) In Search of the Great Penguin.